The History of the Hot Texas Wiener

By

Chef Henry M. Summers

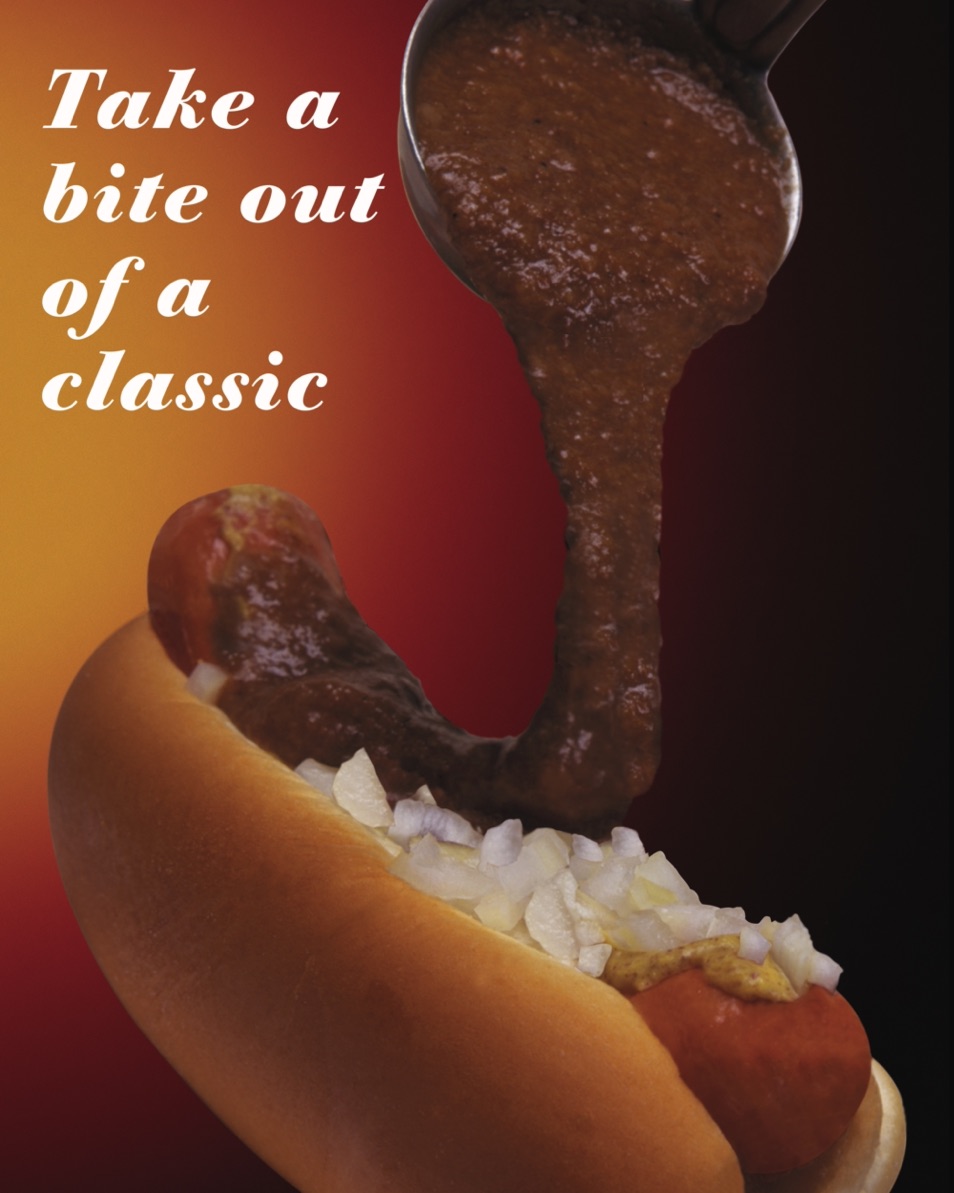

To paraphrase the actor Edmund Gwenn's famous deathbed bon mot, "Hamburgers are easy; hotdogs are hard." This Truth is known to all food stylists. The above portrait of a Hot Texas Wiener, commissioned by the now-defunct Falls View Grill, turned out to be one of the most devilish food styling assignments I ever attempted.

It not only had to look hot and tempting, but do so on the side of a truck lurching up and down Route 46 ferrying supplies between Falls View's four locations, giving it only a fraction of a second in which to make its impression. To make matters even more challenging, all the elements in the photo are in barely contrasting shades of brown.

The solution came in the collaboration of three old friends: my concept, composition and slogan; Jim Lord's photography using one of the most primitive 1 MP digital cameras; and Steven Manowitz's command of Photoshop, that made it possible to clean everything up, and above all, to extend that delectable dribble of sauce beyond what's possible in nature.

My Issue with Hot Texas Wieners

The story below appeared in The (Bergen) Record, June 4, 1980. As far as I know, it was the first newspaper artcle to represent the Texas Wiener as a unique regional delicacy.

All of Paterson's dozen or more Texas Wiener specialists used the same Thumann's hotdog and Pechter's roll (a hotdog roll's quality is judged by its "hinge strength"). But every sauce claimed to have its secret ingredient, and each business's version its special trademark–the original Betts brothers' Falls View Grill on Spruce Street, for example, mixed chopped celery with its raw onion–a popular motif in Greece. Every owner was devoted to producing the finest Texas Wiener he knew how, and each establishment had its core of partisans.

However, and with apologies to all the others, only one could truly be called consecrated–Johnny and Hange's, on River Street and First Avenue. In 1999, decades after the original Johnny and Hange's closed, an eponymous restaurant opened directly across the river in Fair Lawn at 23-20 Maple Ave. The owners bought the rights to the vaunted name in a sheriff's tax lien, and with it, it is said, came the Divine Secret of the Sauce.

Soon afterwards, I reached out to two old friends from Fair Lawn whose qualifications to judge any Texas Wiener contest are beyond dispute: Jersey shore guitar legend Eddie Gamble Trzcinski, and retired Ringwood State Park police officer Marge Gruenler Dzerk. Frankly, all three of us were disappointed. On the other hand, my wife Marilyn, who was weaned from her mother's breast on Johnny and Hange’s All the Way, pronounced the redux indistinguishable from the original.

After a mere decade and a half after the original closed its doors, the emotional wounds bourne by Eddie, Margie and I still may have been too fresh, and got in the way of our objective judgement. Eddie? Margie? Think you can still handle "two away, double french extra-well with sauce, and a large birch?" Ready when you are, my friends.

Many establishments, old and new, continue the tradition, and deserve to be mentioned. But beyond question, the most ancient lineage belongs to Libby's Lunch, serving Hot Texas Wieners at the same location–98 McBride Avenue–since 1936. Libby's was always one of the few Texas Wiener joints with a liquor license, so you can wash your 'dog down with a cold beer (birch beer being the most authentic non-alcoholic alternative), while soaking in the majesty of Paterson's Great Falls–after Niagara, the highest on the east coast of the North American continent.

Founded only in 1962, the Hot Grill can't boast of an ancient lineage like Libby's, or a ringside view of Nature's majesty. But one can't help being awestruck by the ceaseless flow of customers, whose loyalty runs as deep as the gorge beneath the Great Falls. At any hour, the queue seems endless, but moves along efficiently. Nobody ever complains. For that matter, except to put in their order, they barely speak. People do not come to the Hot Grill to shoot the breeze. They have come, some from nothern Bergen County, on serious business. Many Texas Wiener aficionados consider Hot Grill to be the best of the best–the true spiritual heir to Johnny and Hange's.

The Record, June 4, 1980

What confluence of constellations confers incomparable greatness on sparkling wines from the Champagne region of France? What demon or sprite pirouettes upon the branch water, exhalting Kentucky bourbon above all mortal praise? What eternal principle presides over the ancient oak forests of the Périgord, beside whose buried treasure of truffles the rest are mere subterranean fungi? Damned if I know.

What I know is northern New Jersey: her miserably marked and poorly paved roads; her wild and savage shopping malls; her incomparable roadside cuisine. Every day, millions of commuters travel our superhighways on their way to New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and points north, south and west. When hunger compels, they surrender themselves stomach and soul to a malign king with an embossed smile or a terrifying McClown, never to know the Silk City’s singular contribution to international gastronomy: the Johnny and Hange’s Hot Texas Wiener.

Johnny and Hange’s is one of some dozens of fast food joints in and around Paterson specializing in the Hot Texas Wiener. In a purely perfunctory sense, a Hot Texas Wiener consists of a hotdog on a roll with mustard, chopped raw onion, and what is called chili sauce, but is really Greek spaghetti sauce. In the same perfunctory sense, Old Glory is just one of some dozens of national flags, consisting of red, white and blue polyester.

Most people close their eyes when biting into a Johnny and Hange’s Hot Texas Wiener. As the steam penetrates to the ceiling of every sinus, the brain is instantly bathed in pleasure. The first resistance encountered by the teeth is the skin of the hotdog. It bursts, and geysers of exotically spiced meat juices erupt against the palate, completed by the pungency of the mustard and sting of the raw onion, complemented to perfection by the bland foil of the bun.

A few weeks ago, I was dining at one of New Jersey’s most overrated rug joints. Somebody seated at the next table remarked ‘I sure wish we were at Johnny and Hange’s!’ Other diners at nearby tables overheard, and strangers no more, joined in a hossana to Johnny and Hange's.

Johnny Scovish and Angelo ‘Hange’ Mariano opened Johnny and Hange’s on July 4, 1939, with a total investment of $1,500. Within two hours, they had to take money out of the register to buy more food and soda. The pace didn’t slacken through the next 23 years of 18-hour days, seven days a week. Johnny, who died in 1966, and Hange sold the restaurant to Fred Robins in 1962. Robins said that ‘A Saturday doesn’t go by without Hange stopping in with his grandchildren for Hot Texas Wieners. The kids still call it Grandpa Hange’s place.’

Although Robins expanded and modernized the place when he took it over from Grandpa Hange, he hasn’t tampered with the original 41-year old secret sauce recipe. I asked Fred if there was any possibility of dogging the sauce recipe out of him. He replied 'If Gourmet Magazine asked the chef of a large restaurant to divulge a recipe or two, he’ll still have 60 or 70 left. Without Johnny and Hange’s sauce, there wouldn’t be any Johnny and Hange’s! But even if I did reveal the recipe, you would find that without our special equipment, you couldn’t duplicate it.’

In Scovish’s and Mariano’s day, the sauce was cooked on top of the stove for 18 hours. Robin’s $14,000 steam-jacketed kettle has slashed the time to a mere nine hours. ‘When the sauce has finished cooking,’ Robins admonished, ‘it must be aged in our cooler. It’s in this aging process that the final mellowing takes place. If the sauce has not cooled completely before going into the refrigerator, it will become bitter. It must never, never be frozen.’

Instead of using commercial, premixed chili powder, Robins grinds whole spices, and blends them by himself, when everyone else has gone home. He only uses onions of the large, mild Bermuda type. They are chopped, not grated or squeezed into a pulp, by a $5,000 Hobart onion chopper.

The hotdog itself is made by Thumann, and is 60-percent pork and 40-percent beef, with a pinch of semolina added for texture. They have a natural casing, which gives the 'dog that all-important ‘pop' or 'snap.’

The hotdog is deep-fried in pure vegetable oil, which is filtered every night, and used only half as long as most restaurants do. Robins says that the foreign material in unfiltered or overused oil is what gives people agita (Jersey-speak for heartburn). Finally, the dog is served on an old-fashioned paper pulp plate.

Robins started in the food field during a hitch in WW II waiting on tables at the San Antonio Air Force Base. He rapidly rose to the position of Maitre d’. After he mustered out, he went to work as a food consultant to the W.T. Grant store chain. His desire to go into business for himself was only part of the reason he left his job with Grant’s.

‘The president of Grant’s was a genuine hotdog nut,’ Robins said. ‘He went all around tasting different 'dogs, and finally found a brand that he went crazy over. He collared one of his vice presidents, and told him that he wanted to sell this wiener in every W.T. Grant store from coast to coast.’ The vice-president knew this was a mistake, and the experiment failed.

Robins explains that ‘Hotdogs are not like hamburgers. Hamburgers are a neutral food. Chopped meat is chopped meat. But every community has a hotdog of its own, with a distinctly regional taste and texture.'

'For example, in New York, you’d be crazy to try selling any hotdog that wasn’t kosher-style: 100-percent beef, loaded with garlic, with a natural casing. Another reason 'dogs can’t be merchandised like 'burgers is that they can’t be cooked ahead, wrapped up, and placed under lights to stay warm. A hotdog treated in this way would shrivel up in 10 minutes.’

He Was Top Dog in his Day

The precise details are lost in the sauce. But the father of the original Hot Texas Wiener, or at least the man who gave it its name, was John Petrellis, a Greek immigrant who settled in Paterson in the early 1900s.

Petrellis worked for his uncle, who had spent a short time in Texas before moving to Paterson, and opening a hotdog stand in the now-defunct Manhattan Hotel on Memorial Drive (then Paterson Street). At the other end of the block, a joint called Tarapada’s boasted the hottest chili in town. Rounding out the block were nine all-night bars!

Between those salty dogs and that blazing chili, it must have taken the combined pumping power of all nine bars just to keep the flames under control. By all contemporary accounts, however, there was no controlling the rowdy multitudes who reeled in and out of the bars, some, no doubt, carrying their food with them.

All the necessary ingredients were in place, then, for the Hot Texas Wiener to come into existence: Tarapada’s spicy chili; Petrellis’s uncle’s Texas diaspora; and of course, wieners. It is reasonable to conjecture that in all this gastronomical foment, somebody’s chili spilled on somebody else’s hotdog, and Bang! The Original Hot Texas Wiener was born.

Conjecture aside, we know from Joseph Sagarius, who went to work for Petrellis in 1956 and now owns the business, that Petrellis took over his uncle’s hotdog stand in 1920, and gave it the name it still bears today: the Original Hot Texas Wiener. The hotdog stand flourished even during the Great Depression, when Petrellis not only held his price to a nickel, but increased his dog’s size to twelve inches.

‘It was like full-course supper for the workers,' said Sagarius. During the Great Depression, Patrellis became known as a soft touch. His friends often chastened him for giving free Texas Wieners to the hordes of down-and-outers who huddled under the Erie trestle next to Paterson's main post office. ‘They need encouragement,’ Petrellis would plead.

Shortly before Petrellis’s death in 1969, the Original Hot Texas Wiener moved across the street to its present location at 220 Memorial Drive. Today, Sagarius, 69, carries on his predecessor’s tradition, opening the restaurant early in the morning to serve breakfast to bus drivers and city workers, and Texas Wieners to laborers getting off the late shift. Many years later, Patrellis said in an interview ‘Business picked up and we managed to get through the bad times.’