In the 1963 blockbuster hit single “If You Wanna Be Happy,” the immortal Jimmy Soul advises us “Though her face is ugly and her eyes don’t match, take it from me, she’s a better catch.” Linnaeus himself could not have provided us with a more spot-on description of Lophius americanus – the American monkfish.

And a very fine catch she is. But before the early 1980s, most monkfish caught in the waters off New Jersey were destroyed, then unceremoniously tossed overboard. However, when hungry markets were discovered in both Europe and Asia, the species was soon fished to near-extinction.

Thanks to strict regulations adopted in 1998, the monkfish population recovered. And by 2003, this formerly despised byproduct of the scallop dredging industry had become New Jersey’s most valuable fin fish.

A record 3,259 metric tons was taken in 2008, most of it landed at Barnegat Light, with smaller but significant landings at Point Pleasant and Cape May. Today, our monkfish population is considered sustainable. And according to the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, there is no over-fishing at this time.

Unless you are employed aboard a commercial fishing vessel or patronize large Asian supermarkets, you are not likely to see a specimen of this bizarre creature complete with its head. And if you did, you might then refuse to eat it, which would be a great shame.

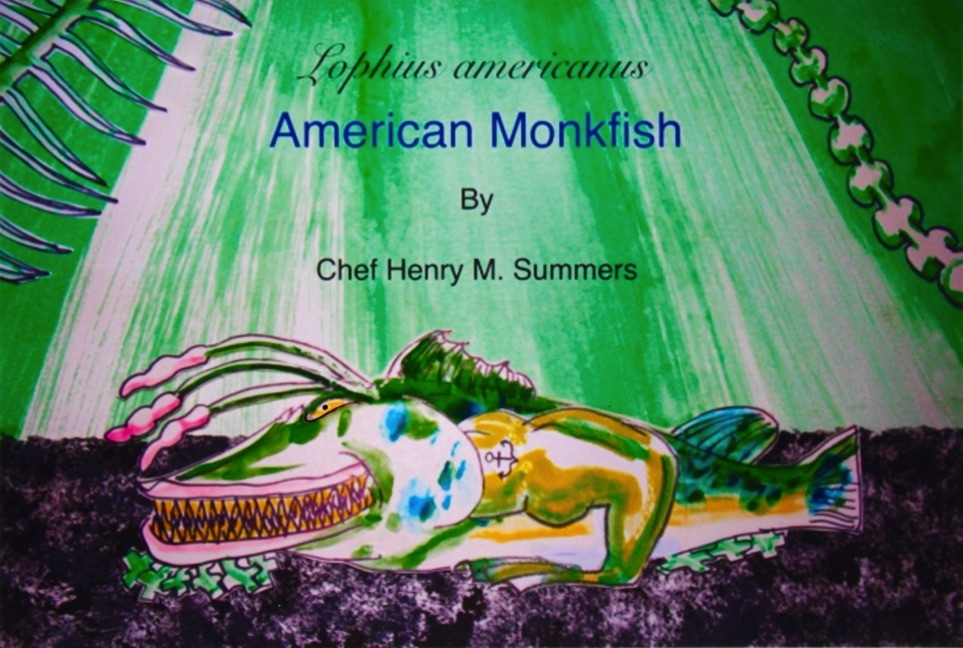

The monkfish goes by many names, including goosefish, belly fish, frogfish, allmouth, sea-devil, but perhaps most befittingly, anglerfish. Blending invisibly with sand, rock and coral, the female monkfish lies perfectly camouflaged on the sea bottom.

the female monkfish lies perfectly camouflaged on the sea bottom

One to three rod-like structures protrude from her spiky head, each terminating in a fleshy appendage called the esca. (In some angler species, this natural fishing lure actually glows with bio-luminescent bacteria.) Our otherwise frozen femme fatale twitches her esca bewitchingly, till some curious fish ventures near . . .

What happens in the next fraction of a second has been called the swiftest strike in all of Nature. Powerful arm-like pectoral fins propel her forward, while in the same instant, this living Charybdis opens her cavernous, tooth-lined mouth, creating an irresistible vortex that sucks her hapless victim inside.

. . . a living Charybdis